A simple way for Python cron tasks to exit if another process is currently running. Does not use a pidfile.

December 2012

1 post

August 2011

1 post

Update 2011-09-27: Turns out virtualenv and virtualenvwrapper support this out of the box. Most of what’s written below is horrifically complex compared to just using the -p switch when you make your virtualenv. You simply need to do this:

$ mkvirtualenv -p /path/to/some/python coolname

That’ll create a new virtualenv called “coolname” that uses /path/to/some/python for it’s Python interpreter. I’ve tested this with PyPy and it worked great.

A recent comment on the original Virtualenv Burrito announcement asked whether it was possible to create virtualenvs using different Python interepreters. The answer is a cautious: yes!

When virtualenv-burrito installs virtualenv, it prevents the virtualenv command from tying itself to a specific interpreter. I wanted to be able to switch between Python versions, creating virtualenvs for each. I haven’t publicized this feature, nor made it easy to use since there may be hidden pitfalls. That said, I’ve not run into any problems.

The way it works is mkvirtualenv uses the same interpreter invoked by the python command to create the virtualenv. For example, normally when I run mkvirtualenv I get a Python 2.7 environment. Using MacPorts, I can switch from my 2.7 default to 2.6 with:

port select --set python26

Now running mkvirtualenv creates a 2.6 environment.

Regardless of what your current default Python interpreter is, once the virtualenv is made, it stays tied to the Python used during creation.

If you don’t have a nice way to switch your default Python, you can still hack it. The key is making the python command use the interpreter you want.

The following1 will also make a Python 2.6 virtualenv even though 2.7 is the default:

Let me know if it works for you. Especially if you are trying out something other than a CPython!

-

A new directory is made with a symlink pointing

pythonto thepython2.6executable. When callingmkvirtualenv, the PATH environment is set with this new directory first so the 2.6 interpreter is used. ↩

June 2011

4 posts

Tired of (yet again) fixing the Elasticfox Firefox extension to work with the latest version of Mozilla Firefox, I finally just made one with an absurd maximum version defined.

You can easily create one yourself. Since xpi files are zip files, it’s something like:

mkdir tangerine; cd tangerineunzip /path/to/elasticfox.xpi- edit install.rdf so maxVersion is

99.0 zip -r9X ../elasticfox-forever.xpi .- drag

elasticfox-forever.xpionto Firefox

Or cop out and click this: elasticfox-forever.xpi

Update 2011-09-23: Using * for the maxVersion still didn’t cut it so I’ve updated the article and xpi file to use a maxVersion of 99.0.

Image modified from I’m with the band by theilr. CC:by-sa.

This is part of the mini-series OpenSSH for Devs.

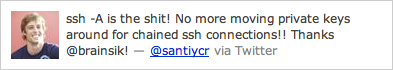

SSH agent forwarding let’s you lock down remote hosts while making them easier to access and use in automated ways. One co-worker succinctly describes agent forwarding as “the shit”.

ExampleSecurely connect to a remote host from a remote host without a password.

laptop:~$ ssh -A host1.example.com

Linux host1 2.6.35-25-server #44-Ubuntu SMP Fri Jan 21 19:09:14 UTC 2011 x86_64 GNU/Linux

host1:~$ scp host2.example.com:some.config .

some.config 100% 1612 1.6KB/s 00:00

host1:~$ logout

Connection to host1.example.com closed.

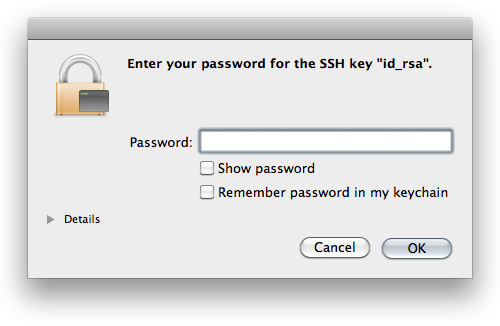

The SSH agent has become so integrated into our local systems many people don’t realize it’s being used. Devs use it daily to avoid having to retype their SSH key1 password every time they connect to a remote host. The typical workflow is:

- Login to laptop

- SSH to a remote host

- Type SSH key password into popup

- No more password typing

The agent serves us by holding onto our private key and transparently authenticating to remote hosts when we connect instead of making us type a password.2

What is SSH agent forwarding?Simply put, agent forwarding allows you to access a remote machine from a remote machine.

Let’s look at the scenario above: connect to host1 and download a file from host2. Without agent forwarding, you’re lucky if you just get to type your password again. If host2 has password authentication disabled or your account has no password set, there’s two options. Option 1: download the file from host2 to your local machine and then upload it to host1. Option 2: upload your SSH private key to host1 and authenticate to host2 using your key password. Compare these to agent forwarding where you run scp and the file is downloaded without question.

If you’ve run into this problem more than a few times, learning about agent forwarding may feel like this:

The SSH agent provides a rare pairing of increased security and better user experience.

From a per-host perspective, you can disable password authentication on all your remote machines and rely on SSH keys for superior auth. Leaked passwords are no longer a vector for unauthorized access since you can’t login with them. Forget about generating random passwords for every user on every new server. If sudo access isn’t needed, don’t set a password at all. If sudo access is required you can get away with reusing passwords, keeping your devops team lean3.

From a network perspective, you ideally want your private servers only accessible via a bastion host or other intermediary. With agent forwarding, instead of this setup being a pain to get into, it’s a single command:

$ ssh -At public.example.com ssh private1.internal

Linux private1 2.6.35-25-server #44-Ubuntu SMP Fri Jan 21 19:09:14 UTC 2011 x86_64 GNU/Linux

private1:~$ logout

Connection to private1.internal closed.

Connection to public.example.com closed.

Agent forwarding can be turned on via the command-line by passing -A or via your SSH config by setting ForwardAgent yes.

I’d be negligent if I didn’t recommend setting this only for hosts you trust. While it’s not possible to steal a private key through an agent, it’s trivial for a malicious root user to login to remote hosts with your public key.

Is there another way you use SSH agent forwarding? You should post a comment or send me a message.

-

This article assumes you already use an SSH key to access remote hosts. If you don’t, send me a note. If I get enough questions about SSH keys, I’ll do a writeup on them. ↩

-

Some systems aren’t setup with an askpass program and the agent running in the background. In those cases, some devs will generate their SSH private key without a password to get the effect of not needing to type in their password for every SSH connection they make. Regardless of the security implications, that setup loses a beneficial feature of SSH: agent forwarding! ↩

-

Buzzwords aside, having to search for a password randomly generated 2 months ago before getting on with your task is sure way to wipe stored state and kill a task’s momentum. ↩

This is part of the mini-series OpenSSH for Devs.

An SSH config let’s you set options you use often (e.g., the user to login as or the port to connect to) globally or per-host. It can save a lot of typing and helps make SSH Just Work.

ExampleInstead of typing:

ssh -p734 teamaster@sencha.example.com

You can type:

ssh sencha

By having this in your ~/.ssh/config:

Host sencha

HostName sencha.example.com

Port 734

User teamaster

In your home is a .ssh directory. This is where your SSH keypair and known_hosts1 files are. This directory is not made of unicorns. Create a file named config and your SSH tools2 will use it’s settings.

If your laptop username is different than the one on your remote hosts, create it with:

User jon.postel

If you use a non-standard SSH port to avoid the bots, create it with:

Port 22022

Have different settings for different hosts? No problem. Just keep in mind the first match wins and put specific settings before generic ones:

# ancient box we never upgraded

Host host1.example.com

User oldusername

# still on port 22

Host *.example.com

Port 22022

ForwardAgent yes

# defaults for all hosts

Host *

User bofh

You’re probably familiar with the dance you do when connecting to a host for the first time:

$ ssh host1.example.com

The authenticity of host 'host1.example.com (192.0.2.101)' can't be established.

RSA key fingerprint is 39:9b:de:ad:9e:be:ef:95:ca:fe:1b:53:b0:00:00:b5.

Are you sure you want to continue connecting (yes/no)?

It looks impressive, but it’s worthless. If you’re worried about man-in-the-middle attacks, there are much better things to do. Start by disabling password authentication3 and require people to have an SSH key on the server. Expecting people to check these hashes means you’ve already failed.

To get rid of the dance add something like:

Host *.compute-1.amazonaws.com

StrictHostKeyChecking no

First time connections will give you a warning, but you’ll make it in.

AliasesYou can create aliases4 by using Host to match a name and HostName to say where to connect.

Host web1

HostName ec2-192-0-2-42.compute-1.amazonaws.com

The advantages over modifying /etc/hosts are you don’t need to be root and SSH will use the same host key for web1 and ec2-192-0-2-42.compute-1.amazonaws.com. The disadvantage is that only SSH tools see this. For example, your browser has no idea web1 is an alias for that EC2 host. Because of this, I sometimes create both the SSH alias and hosts entry for the best of both worlds.

There are a lot of options, but these are the ones I’ve seen used most:

- Host — Matches the hostname argument. Accepts patterns and causes options following it to apply only to hosts matching the pattern.

- User — Username to connect with.

- Port — Port to connect to.

- ForwardAgent — Set to

yesto turn on SSH agent forwarding. - StrictHostKeyChecking — Set to

noto skip the “authenticity of host” dance. - HostName — Server to connect to. Used to create an alias from Host to another remote server.

Do you have a favorite option not mentioned here? You should post a comment or send me a message.

-

The

known_hostsfile contains the keys for all the remote hosts you’ve connected to. The stored key is compared to the remote key when you connect to warn of a man-in-the-middle attack. ↩ -

ssh,scp,sftp,sshfs, well-written paramiko based Python tools, and probably more. ↩ -

In the server’s

sshd_configsetPasswordAuthentication no. Contact me if you are interested in a post on securing the SSH server. ↩ -

I made this term up. There may be a better one. ↩

There have been many surprises as I’ve moved from Sysadmin to Coder. Some of them are a product of switching contexts: what was once “common knowledge” is now “tips & tricks” (and vice versa). One tool that has regularly come up is SSH. It can be painful to watch developers jump through unnecessary hoops (over and over again) in order to access remote hosts.

In that light, presented here is a short series of posts covering useful OpenSSH features for developers. My peers and I use these everyday and it’s made our jobs easier.

- SSH Config

- SSH Agent Forwarding

- SSH Tunnels check back soon

May 2011

2 posts

Starting with the punk rock creation story, discusses the fascinating, proven, theorem that you can’t have all three of consistency, availability, and partition-tolerance in a distributed system.

A very interesting follow-up is: A CAP Solution (Proving Brewer Wrong). It approaches the problem by dynamically guaranteeing different CAP properties instead of trying to guarantee them all at once.

This Python breakfast just got tastier. A major update to the way Virtualenv Burrito works was released this weekend. There is now full support for extension points and a less hackish way of managing the packages1 under the hood.

Already have Virtualenv Burrito installed? Run this:

virtualenv-burrito upgrade

New to Virtualenv Burrito? Read about it or run this:

curl -s https://raw.github.com/brainsik/virtualenv-burrito/master/virtualenv-burrito.sh | bash

Virtualenv Burrito’s goal is to have a working virtualenv + virtualenvwrapper environment with just one command. Read about it on Github or see the original announcement.

March 2011

1 post

Over the weekend I finished1 a tool called Virtualenv Burrito. It’s goal was to be a single command which would setup Virtualenv and Virtualenvwrapper so you could start hacking on Python projects as quickly as possible. As a bonus, it installs the virtualenv-burrito command which will upgrade those packages to the latest versions I’ve tested.

Virtualenv Burrito was inspired by Pycon sprinters wasting precious time setting up virtual environments instead of sprinting. For many people, it’s sadly complicated to get a virtualenv + virtualenvwrapper environment. The worst part, it’s almost always yak shaving in the way of a real goal.

No more! To have a working virtualenv + virtualenvwrapper environment, run this command2:

curl -s https://raw.github.com/brainsik/virtualenv-burrito/master/virtualenv-burrito.sh | bash

That’s it. Whenever you login, you’ll have the full arsenal of virtualenvwrapper commands at your disposal.

Virtualenv quickstartCreate a new virtualenv:

mkvirtualenv newname

Once activated, pip install (without using sudo) whichever Python packages you want. They’ll only be available in that virtualenv. Make as many virtualenvs as you like.

To switch to another virtualenv you’ve created:

workon othername

To get the latest tested virtualenv + virtualenvwrapper packages:

virtualenv-burrito upgrade

The real hard work is done by the creators of Virtualenv and Virtualenvwrapper. Virtualenv is maintained by Ian Bicking. Virtualenvwrapper is maintained by Doug Hellman.

-

For this release, extension points (e.g., postactivate) are not supported. While this doesn’t affect the project goal of getting people coding quickly, it’s a cool feature, and (more importantly) I need it for work. :-) I’ll be adding support soon and making it available via

virtualenv-burrito upgrade. ↩ -

Truth be told, I think piping the web into your shell is insane. Be safe, and read the code. ↩

February 2011

7 posts

Gorgeous illustrations for the 5 Best Film nominees. Also see his BAFTA mask illustration used for the tickets.

Paul Vanoue’s Latent Figure Protocol “utilizes known sequences in online [DNA] databases to produce ‘planned’ images” of ☠ and ©. Fantastic work!

"A trained civil engineer, he then turned the hole into a kidney-shaped swimming pool, flourished with a fine biomorphic indentation."

Disturbing and intriguing.

Although it’s been a few years since I switched from full-time Sysadmin to full-time Coder, being in a startup means getting saddled with an opsy task now and again regardless of your “title”.

The problem: We bought a bunch of servers which need minimal OS, IP and a hostname before they’re racked. In otherwords, we want to drop them in a datacenter, turn them on, and leave knowing there’s remote SSH access. Data centers are environmentally hostile (hot rows, cold rows, too loud). It’s ideal to get in and out as quickly as possible and do any remaining config while listening to music and having a cup of tea.

The solution: An automated Ubuntu install using preseeding. One goal is to get a solution setup as quickly as possible. We don’t have 100s or 1000s of servers that need install, but we don’t want to setup temporary network infrastructure, and we don’t want all the developers (there’s not many) sitting around hitting <enter> every few minutes. In my past life I may have gone for netbooting and a DHCP server handing out the IPs and hostnames, but this life lead to the shorter road of burning an Ubuntu Server disc with a preseed file.

Open an existing Ubuntu Server image and copy it’s contents somewhere. I used rsync -a to copy the image volume to my drive. This directory is the contents of the new disc image. All that’s needed is a preseed file and modifying the boot config to load it.

Start with the example Maverick preseed file. The comments are good so you can get most of the way just going through it. However, I ended up in a short trial and error process to get it fully baked.

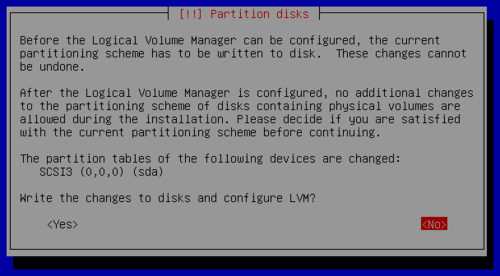

Gotcha 1: LVM partitioningDuring LVM partitioning, the install got stuck while waiting for confirmation on “Write the changes to disk and configure LVM?”:

Set this undocumented (AFAICT) option:

d-i partman-lvm/confirm_nooverwrite boolean true

Althought this doesn’t stop the install, it takes a while for Apt to give up trying to contact the host. To keep things speedy, disable it by setting a null security repo host:

d-i apt-setup/security_host string

With all the Apt repositories disabled, no useful lines are added to /etc/apt/sources.list. This doesn’t matter too much if next you’ll be running an install script on the box (fix the sources.list in the script), but if not, it’s an annoying yak you’ll shave when you want to upgrade or install a package. Regardless, it’s so easy to make it right, you might as well:

d-i preseed/late_command string echo 'deb http://us.archive.ubuntu.com/ubuntu/ maverick main restricted universe multiverse' >> /target/etc/apt/sources.list; echo 'debhttp://us.archive.ubuntu.com/ubuntu/ maverick-updates main restricted universe multiverse' >> /target/etc/apt/sources.list; echo 'deb http://security.ubuntu.com/ubuntu maverick-security main restricted universe multiverse' >> /target/etc/apt/sources.list

Your preseed config is done so save it to preseed/local.seed (or whatever/wherever) in the directory you made.

To make the CD use your seed on boot, modify isolinux/isolinux.cfg to timeout quick and use the file you saved. Mine looks like this:

# D-I config version 2.0

include menu.cfg

default autoinstall

prompt 0

timeout 1

ui gfxboot bootlogo

LABEL autoinstall

menu label ^Minimal autoinstall

kernel /install/vmlinuz

append preseed/file=/cdrom/preseed/local.seed debian-installer/locale=en_US console-setup/layoutcode=us localechooser/translation/warn-light=true localechooser/translation/warn-severe=true initrd=/install/initrd.gz ramdisk_size=16384 root=/dev/ram rw quiet --

To make a bootable ISO you’ll need mkisofs. If you’re on Mac OS X (like me) you can use MacPorts — sudo port install cdrtools — or the hipster package manager1, Homebrew. Once you have the tool you need, just follow this command-line:

mkisofs -r -V 'Ubuntu Autoinstaller' -cache-inodes -J -l -b isolinux/isolinux.bin -c isolinux/boot.cat -no-emul-boot -boot-load-size 4 -boot-info-table -o custom_ubuntu_autoinstaller.iso /path/to/your/files

And … your done. Use Virtualbox to test the boot image and tweak the preseed file to make it do what you want. Don’t forget to re-run the mkisofs command whenver you change the seed or isolinux.cfg files!

-

Just kidding. I’m a fan of mxcl’s projects. Got Audioscrobbler.app running right now! ↩